Recently I was browsing the DFIR.training CTF section and found a nice network forensics challenge released by Andrew Swartwood in December 2017 called TufMups Undercover Operation.

We are given a PCAP to analyse, and the following briefing:

You’re an agent with a government law enforcement agency. You’ve been tracking a group of criminal hackers known as “TufMups”. This group either keeps a low profile, your agency’s capacity to run investigations on the internet is very poor, or some combination of those two factors. Up until two days ago you had an active relationship with an informant who went by the handle “K3anu”. As you walked into your office you received a package containing a flash drive, a printed screenshot (at the top of this blog post) and a very short note.

“Review this PCAP. It will all make sense. Woaaahhhh. – K3anu”

That package was the last you heard from K3anu.

Let’s download the PCAP and get started then.

01 – What is the start time of the PCAP (“Date and Time of Day” setting in Wireshark round to nearest second)?

After extracting the PCAP file and opening it in Wireshark, we can bring up the Summary window to find the start and end time of the capture. One thing I’m not sure about is the timezone – it’s not explicitly specified. My SIFT VM and Wireshark are both set to UTC so let’s assume that for now.

2017-12-10 22:43:17

02 – What is the end time of the PCAP (“Date and Time of Day” setting in Wireshark round to nearest second)?

The Summary screen also gives us the end time of the capture. Again, assuming UTC as no timezone is specified and that’s what I’m working with locally.

2017-12-10 23:25:19

03 – How many total packets were sent between the host and the hacker website IP?

Using the Endpoints screen we can quickly summarise the traffic sent between each IP address in the capture. We know from the provided screenshot that the server we are interested in has the IP address 104.131.112.255

By checking against our IP of interest we can see that 15,128 packets were exchanged.

15,128

04 – What is the hostname of the system the PCAP was recovered from? (all caps)

Hostnames aren’t always going to be available in PCAPs, at least not directly. In this case we can filter for DHCP traffic and examine any requests that have been captured.

We only have one DHCP request in our capture and it matches the IP address of our capturing system. Examining the packet details we find the hostname:

MSEDGEWIN10

05 – What exact version of browser did K3anu use? (exact number only)

We can find the web browser user-agent string by filtering for HTTP requests made by K3anu’s system:

http and ip.src==10.0.2.15

Examining a request gives us the following string:

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/63.0.3239.84 Safari/537.36

There are a few ways to decode this to find the browser version; I used CyberChef.

K3anu was using Chrome 63.0.3239.84

63.0.3239.84

06 – What operating system did K3anu use? (Name and number only)

We already have the answer to this from Question 5:

Windows 10

07 – How many DNS queries in the PCAP received NXdomain responses?

We can filter for DNS packets where the Response Code is set to 3, indicating that the domain did not exist.

dns.flags.rcode == 3

5 responses

08 – What is the hidden message in the TufMups website? (decoded)

If the TufMups website were still online we could simply visit it and take a look. Unfortunately it was offline when I did this CTF but we can use our network forensics skills to find out what it looked like.

By filtering on HTTP traffic between K3anu’s system and the TufMups server, and following the HTTP Stream (#2879), we can see the HTML source including an interesting comment.

bH56Kml4b255Kmt4byp6O21tcyolKnhjem1lZHBl

From the character set this looks like base64, but decoding it only gives us:

l~z*ixony*kxo*z;mms*%*xczmedpe

Maybe it is encrypted rather as well as encoded. CyberChef has a collection of cipher functions that we can try, including an XOR Brute Force module. By default the module will attempt single-byte keys and display the output.

CyberChef for the win.

ftp creds are p1ggy / ripgonzo

09 – What is the key to decode the secret message in the TufMups website?

From our work on Question 8 we know the key:

0a

10 – How did K3anu get access to the file? (lowercase, just protocol)

The hidden message in the TufMups website mentions FTP credentials, so that is a good starting point. We can filter on FTP traffic, and follow the TCP Stream (#4075) for easier reading.

We can see that two files were downloaded to K3anu’s machine – decrypttool.exe and mupfullz2017.zip. Those are probably worth remembering for later.

ftp

11 – What’s the nickname of the operator on the IRC channel?

Similarly, we can filter on IRC traffic and follow the TCP Stream (#2930) for easier reading.

IRC operators typically have @ before their nickname so they can be identified.

k3rm1t

12 – What is the 1st operation needed to decode the IRC users “secure” comms? (just the format name)

Scrolling through the IRC chat between K3anu and the TufMups we see a few messages that stand out. With context from the questions, there are four steps required to make them legible.

The first message is:

MnIgMnEgMnIgMnIgMjAgMnEgMnEgMnEgMjAgMnIgMnEgMnIgMnIgMG4gMnEgMjAgMnIgMnIgMnIgMnIgMjAgMnIgMnIgMjAgMnIgMnIgMnIgMG4gMnEgMnIgMnIgMjAgMnIgMnIgMnEgMjAgMnEgMnIgMnIgMjAgMnIgMG4gMnIgMnIgMjAgMnIgMnIgMnIgMG4gMnIgMnEgMG4gMnEgMnIgMnEgMnIgMjAgMnEgMnEgMnEgMjAgMnIgMnEgMnEgMnIgMG4gMnIgMnIgMnEgMnIgMjAgMnEgMnEgMnEgMjAgMnIgMnEgMnIgMG4gMnIgMnIgMnIgMjAgMnIgMnIgMnEgMjAgMnIgMnEgMnIgMjAgMnI=

From the character set (and because it’s almost always the first thing I try) let’s assume base64 encoding.

base64

13 – What is the 2nd operation needed to decode the IRC users “secure” comms? (just the format name)

Our result from Question 12 looks like Hex encoding, but the character set has been shifted. Using CyberChef we can easily apply rot13.

rot13

14 – What is the 3rd operation needed to decode the IRC users “secure” comms? (just the format name)

From here CyberChef actually does the work for us, and suggests that applying the From Hex then From Morse Code operations will give us human-readable output.

Let’s try it!

Hex

15 – What is the 4th and final operation needed to decode the IRC users “secure” comms? (2 words lowercase)

morse code

Now that we know the required steps we can decode the remaining “secure” messages in the captured IRC chat.

LOL THIS DUDE IS A COP FOR SURE

LET'S PWN HIM AND FIND OUT WTF HES UP TO

HAHAHA FOR SURE

ALRIGHT I'LL GIVE HIM A FAKE LEAD AND PAYLOAD

HES A COP LETS KILL HIM AND DUMP HIM IN THE USUAL SPOT

WITH PLEASURE, ILL SEND ANIMAL

It’s not looking good for K3anu!

16 – What is the password to decrypt the zip file that was downloaded by K3anu?

The TufMups have given K3anu a test – decrypt a file from their FTP server. In Question 10 we saw K3anu download two files from the TufMups FTP server; we need to extract them from the PCAP.

Filter on ftp-data to show the file transfer traffic, then follow the TCP Stream for the ZIP file (#4079)

Select the Raw radio button and Save As. We have our ZIP file, but we need a password to open it.

There are a few tools capable of cracking ZIP passwords; my goto is John The Ripper.

First, we use the zip2john utility to extract the hashed password from the ZIP.

zip2john ~/tufmups/mupfullz2017.zip > ~/tufmups/mupfullz2017.zip.hash

Then, use John with the RockYou wordlist to crack the extracted hash.

john --wordlist=/opt/wordlists/rockyou.txt ~/tufmups/mupfullz2017.zip.hash

It doesn’t take John very long to churn through the wordlist and find a match:

fozzie

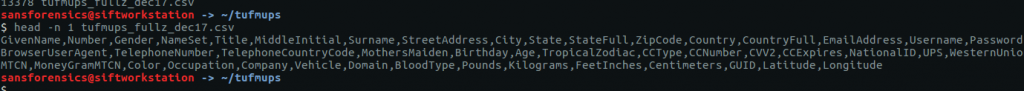

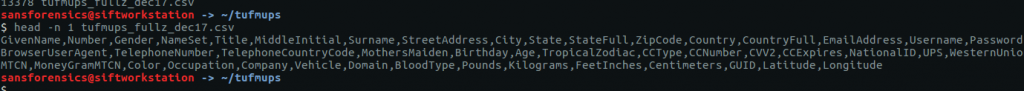

17 – How many total rows of “fullz” are represented in the file?

After extracting the ZIP file we are presented with a CSV – tufmups_fullz_dec17.csv

We can check the number of lines in the file with a simple bash command

wc -l tufmups_fullz_dec17.csv

head -n 1 tufmups_fullz_dec17.csv

Subtracting one row to account for the column headers, we have 13377 rows of “fullz”.

13377

18 – How many people in the fullz are named Joshua, have a MasterCard, and use an OS X system?

This can be solved with a bit more command-line work; using grep to filter only the characteristics we are looking for, and wc to count the matching rows.

cat tufmups_fullz_dec17.csv | grep -i "joshua" | grep -i "mastercard" | grep -i "os x" | wc -l

12

19 – From the previous question (people named Joshua) – what is the most expensive car new in this filtered list?

Modifying the command from Question 18 slightly, we can get a list of cars by filtering out the “Vehicle” column (column 37).

cat tufmups_fullz_dec17.csv | grep -i "joshua" | grep -i "mastercard" | grep -i "os x" | cut -d "," -f 37

After a bit of Googling I found the answer:

2006 Pagani Zonda

20 – What IP and port does the executable connect to? ip:port

Remember K3anu downloaded decrypttool.exe from the FTP server as well as the ZIP file? And how the TufMups were going to feed some false data to confirm their suspicions? We’re getting back to that now.

Using the same technique as for Question 16, we can extract decrypttool.exe from the PCAP (TCP Stream #4077)

There are a few ways to tackle this now that we have the binary. If you have a Windows VM set up for malware analysis you could just execute the binary and track its activity. Instead, I calculated the MD5 hash (20422a060c5f8ee5e2c3ba3329de514f) and searched a public online sandbox for a quick win.

md5sum decrypttool.exe

It’s important to note that I searched for the hash of the binary. In general I do not upload potentially malicious binaries to a public sandbox. It may not make a huge difference in a CTF, but in a real-world incident response uploading a potentially malicious binary can tip-off an attacker that they have been detected. In this case, the binary had already been uploaded to the sandbox on 17 December 2017 – roughly 12 days before the CTF was posted online – and the resulting analysis including details of a network connection was available for inspection.

104.131.112.255:1234

22 – What was used to compile the malicious executable?

This one took me quite a bit longer than I expected and I ended up taking a guess. Given the numerous references to Python in the Dropped Files section of the sandbox analysis, and in the output of the strings utility, I guessed PyInstaller.

PyInstaller

23 – What executable did K3anu likely use to download files from the remote server? (exactly as written in source material)

We know that the TufMups found out about K3anu’s real identity, and that K3anu downloaded an executable that connects back to the TufMups server on an unusual port. Let’s see if there is anything in the PCAP to shed light on what the TufMups found.

Filter for traffic on the IP address and source used by the TufMups binary.

ip.addr == 104.131.112.255 && tcp.port == 1234

Follow the TCP Stream (#4082) for easier reading. Our malicious binary is acting as a reverse shell into K3anu’s machine!

Reading through the stream we can see a list of running processes. Based on the process names, the only dedicated FTP client is WinSCP.exe

WinSCP.exe

24 – What is the host system’s exact BIOS version?

We can use the same TCP Stream (#4082) to answer the next few questions as well. The output of the systeminfo command lists the exact BIOS version.

innotek GmbH VirtualBox, 12/1/2006

25 – What is the filename of the first file taken from K3anu’s computer?

We can see two files being exfiltrated back to the TufMups server; trueidentity.zip is the first of the two…

C:\Users\IEUser\Desktop\trueidentity.zip

26 – What is the filename of the second file taken from K3anu’s computer?

…and the second is trueidpwhelp.zip

C:\Users\IEUser\Desktop\trueidpwhelp.zip

27 – What utility was used to steal the files from K3anu’s computer?

The files were transferred using ncat.

ncat

28 – What destination port was used to steal the files from K3anu’s computer?

The ncat connection was established to port 1235.

1235

29 – What is the password to decrypt the file stolen from K3anu’s computer? (it’s lowercase)

There were two ZIP files transferred from K3anu’s machine – trueidentity.zip and trueidpwhelp.zip – extract them both from the PCAP using the same technique as Question 16 and Question 20.

I started with trueidpwhelp.zip – which didn’t require a password – and contained two images of airports. The Comment field in the EXIF data gave a clue…

My guess was that the IATA airport codes for the respective images would lead to the password for trueidentity.zip, but I don’t have time for OSINT. Let’s try cracking the password first.

Same procedure as Question 16. First run zip2john to extract the hash, then john itself to perform the cracking.

zip2john ~/tufmups/trueidentity.zip > ~/tufmups/trueidentity.zip.hash

john --wordlist=/opt/wordlists/rockyou.txt ~/tufmups/trueidentity.zip.hash

Using the RockYou wordlist once again, it doesn’t take long to crack the password hash.

molder

30 – What is K3anu’s real identity?

The trueidentity.zip file contains three images. Once again, the EXIF data reveals more clues about K3anu’s identity. Examining constantine2.gif give us the following.

My true identity is constantine, eternal enemy of Kermit the frog AKA k3rm17 of TufMups.

31 – What city is K3anu likely to be in?

This time it’s the EXIF data from constantine3.jpg that is of use to us.

Generally the TufMups have their enemies shipped to 42.226391, -8.899541

I guess we have to do a little bit of OSINT after all. Plugging the coordinates into Google Maps give us the following location:

The city isn’t immediately obvious, but with a bit of digging the closest city appears to be Pontevedra, Spain.

Pontevedra

32 – What is K3anu’s likely status? (lowercase)

The EXIF data from Constantine1.jpg gives us our answer.

If you've found this I'm already dead, killed by the vicious muppets of TufMups.

33 – What is the address of the restaurant closest to where K3anu is likely to be? (exactly as reported by Google maps)

Back to Google Maps.

Camino C5 Illas Cies, 8, Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain

34 – The hacker left a message for law enforcement on K3anu’s system, what was it? (message only)

Reading to the end of the traffic sent by decrypttool.exe (TCP Stream #4082) we can see the final message left for the investigators.

yeah good luck finding this guy cops, great job picking an informant.. real winner with his grilled cheese

Woaaahhhh, indeed.